Dental Ethics, History of Medical Bioethics, and Philosophy in Dentistry

- History of Medical Ethics

- Dental Ethics: Review of Bioethical Principles

- The Case Against Bioethical Decision-Making Model

- Philosophical Exploration of Dentistry

- Ethics

History of Medical Bioethics

Medical bioethics has a long history from ancient times. We are, however, left with vague memes in the medical and dental communities. Healthcare professionals are given diluted overviews and casuistic decision making models in schools. Ethics is a rich field of study that promotes moral independency and agency. The goal of this section is to spread better understanding of ethical principles through history and philosophical connection.

Hippocratic Oath

Health professionals take an oath during school that establishes them as part of a profession. Many of these oaths are related to the one Hippocrates gave to his students in ancient Greece. As the father of medicine, Hippocrates had great influence in establishing memes like “do no harm” in the medical and dental fields. All doctors recognize of the importance of health and to put the patient first.

Not all doctors take the same oath, however, and not all doctors are required to consent to its stipulations. The original Hippocratic oath made doctors swear to Apollo and promise never to do surgery (not as safe as today). Health professional oaths are current to medical advances but individualized to each school. An unstandardized oath inhibits consistent communication amongst medical professionals.

Also, there is little justifiable reason to expect a doctor to follow an oath that is not understood or consented to. Everyone does what she believes to be the best thing to do. A doctor can be given rules to follow by authority figures. If she doesn’t believe in them, she will only follow the rules out of fear of authority or punishment. Doctors are moral agents, not instruments of moral bureaucracy.

Nuremberg Trials

The Nazi medical experimentation is the worst case of doctors simply following orders and acting for the greater good. People where placed in barometric chambers, for example, to learn the effects of extreme pressure conditions. Much of our early understanding of deep sea and space exploration comes from these medical experiments. Using knowledge gained through unethical experimentation is still a highly debated topic today.

The holocaust was gross violation of human dignity. The Nuremberg Code was a direct reconciliation of the Nazi doctor trials. It expressed the utmost respect for patient consent and reduction of human suffering. You can see the direct influence on how human clinical trials are evaluated by The International Review Board.

Most doctors aren’t doing experiments, but some ethical considerations of research still apply to doctors when testing out new procedures and technologies. We also do not want dentists forcing treatment like when Nazi dentists forcefully removed gold restorations from prisoners. Patient well-being and consent in western bioethics due to unethical medical experimentation done historically.

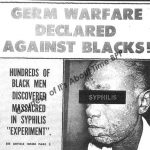

Tuskegee Experiments

Lessons from history are soon forgotten, sad to say. Until 1972, the medical community intentionally kept around 400 black men untreated for syphilis. The study went for 40 years. Even though there was a cure, the doctors misdirected infected patients to see the longterm side affects. This study violated standards of racial and economic justice because it deliberately targeted poor, uneducated black farmers.

The problem did not consist of a few bad apples. The study was recognized for awards upon publication in a medical journal. The experiment was also openly discussed by medical professionals in major government departments and national organizations. Gross violations of human right is not a problem of the distant past.

The Tuskegee Experiments makes aware of how intersectionality is important in ethics. Patients in the study were not chosen merely because they were uneducated or black. They were chosen specifically because they are poor, black, and male. These societal categories are used to justify violations of autonomy.

The Belmont Report

Published in 1978, the Belmont Report outlines the four ethical principles intended mainly for medical research. Medical schools adapted the principles for medical students and dental schools for dental students.

The benefit of the bioethical-decision making model is that it offers a central standard independent of the different religious, political, and cultural values students are brought up with before entering the medical and dental fields. The model is also casuistic enough that students can still express their religious, political, and cultural opinions in discussions. The authors of the Belmont Report even acknowledge that the principles are just a guide because they often contradict each other.

Below is an explanation of the four bioethical principles used in medicine and dentistry. Its casuistry makes it versatile for healthcare professionals but philosophically problematic.

Review of Bioethical Principles

Dental professionals should be aware of the following bioethical principles in dental ethics:

- Justice – treat everyone fairly and equally

- Beneficence – maximize patient well-being and professional expertise

- Maleficence – minimize suffering and do no harm

- Respect for Autonomy – consider the patient consent

Some ethicists like to include veracity, confidentiality, etc. in the list. These extras, however, are not universality recognized by medical professionals or derivatives of the above four principles. The next few sections explain the four main bioethical principles in dentistry. Readers will become aware of the casuistry of bioethical analysis upon further reading.

Justice

Plato discusses how a just man behaves in The Republic, the greatest work of western philosophy. Justice is historically conceived as a type of virtue, a character trait that promotes flourishing when nurtured. For Plato, justice is a type of regulation amongst the different castes in a state towards its betterment or amongst the psyche of the man toward happiness. He rejected the traditional conception of justice, help your friends and harm your enemies. Plato claimed that justice, as a virtue, only improves so never involves harm. Everyone seeks to live life well, so every one must seek to be just.

Today, most people are familiar with justice as a form of judicial resolution or socioeconomic redistribution. The law dictates that one should not discriminate based on race, gender, etc. One must remember that things like slavery were legal and some laws contradict each other. Some laws are unjust and a just man never follows an unjust law.

Justice is sometimes synonymous with core values like equality or fairness. To promote equality, we may try to redistribute wealth by offering free services to the disenfranchised. Others might find this policy to be unfair since it may benefit free riders or devalue productivity. It is obvious that different policies may seem just or unjust depending on competing conceptions of justice.

Beneficence

We all have a duty to always the right thing. However, this is different from doing good or helping. You can help a theft commit a crime, but this is obviously not a moral thing to do. The principle of beneficence reminds us to help others, but we not not morally required to help everyone in every particular situation. We must draw a distinction between moral good (what we must ethically do) and beneficiary good (what we can do to help).

While being altruistic does not necessarily mean being moral, being selfish does not mean you are being immoral. Often dentists will provide free treatment to deserving patients. If a dentist only provided free treatment, her practice would soon go bankrupt and she could not help anyone. Aristotle pointed out that a friend to all is a friend to none. Dentists must invest in themselves and their businesses.

Kant characterized the duty to help others as an imperfect duty. An imperfect duty is one that can obligate us but does not in every situation or time. The principle of beneficence reminds us that we should help others as mush as we can. However, it does not specify when we must do so and to what extent.

Maleficence

The principle of non-maleficence reminds healthcare professionals that they should reduce pain, suffering, and harm. There is a clear difference between hurting someone and harming them. A dentist hurts a patient when she gives injections for surgery, but doesn’t harm a patient overall when an infected tooth is extracted. While pain involves sensory nerve transduction, harm involves a patient’s wellbeing.

Pain is sometimes a psychological response of the body. It can tell a patient she needs to see a dentist. Doctors can even stimulate pain fibers to facilitate healing. The complexity of dealing with patient pain involves evaluating its subjective conscious experience. Different amounts of stimulus corresponds to different levels of pain experience. Even individuals of different genders and cultures deal with pain differently.

Hippocrates decries that health professionals should never do harm. When you nurture a patient back to health, the person returns to function. When you harm a patient, their well-being diminishes. Harm reduces another person’s ability to function and live life well. Many philosophers think that the purpose to life is to maximize happiness or well-being. Since, harming is the exact opposite of how one should act, we should never do any harm. Measuring maleficence is difficult since people feel differently about pain and what things cause harm.

Respect for Autonomy

In greek, autós stands for self and nómos stands for law. To be autonomous is to live life by one’s own laws. This is not to say one cannot listen to others. To act heteronomously (hetero meaning other) is to merely obey orders blindly. To act autonomously is to understand the necessity of proposed ethical rules and to act upon them with motivated intention.

Kant claimed that people act as free autonomous agents not by just following any old rule but the moral law. One formulates a moral principles placing oneself as the legislator of the moral law through a rational will. One evaluates if the rule is morally obligatory using practical reason and acts upon it once recognizing first hand a rule that one must actually follow. Rules that all moral agents must follow are categorical imperatives.

Kantian ethics provides a rational bases for respecting autonomy (its obligatory to all rational agents). The principle of respect for autonomy usually states that a provider must value the deliberative process of the patient including arbitrary preferences, emotions, or opinions. We must also respect those with diminished autonomy (children, unconscious, etc.). It is easy to understand that this principle avoids forced treatment like in the holocaust. However, if we are following a rule merely to avoid consequences, then we must admit that there actually is no rational reason to respect or value such a rule categorically (in and of itself).

The Case Against Bioethical Decision-Making Model

The bioethical decision-making model consists of a guide to problem solving in clinical situations for healthcare professionals. The guide is too vague to answer complex moral dilemmas and there is not reason why one must follow any of the principles in the first place. Let us first look at the steps of the model.

Bioethical Decision-Making Model

- Identify the ethical dilemma

- Outline different possible solutions to the dilemma

- Consider the four bioethical principles

- Evaluate which ethical principles conflict in each solution

- Consider legal implications

- Act upon the solution that uphold bioethical principles

Example Scenario

Patient requires crown lengthening for adequate restoration of a tooth with a crown. The patient wants the crown but rejects crown lengthening due to cost. Three possible solutions to this treatment plan dilemma come to mind:

Solution 1:

Only restore upon full acceptance

Justice: n/a

Beneficence: refusal of care

Maleficence: avoids causing perio issues

Autonomy: n/a

Solution 2:

Just do the crown

Justice: n/a

Beneficence: n/a

Maleficence: causes perio issues

Autonomy: follows patient’s decision

Solution 3:

Do the crown lengthening for free

Justice: is not fair to paying patients

Beneficence: free service to patient

Maleficence: n/a

Autonomy: n/a

Bioethics is an Arbitrary Moral Decision-Making Model

Three different people can view this same situation and each would go for a different possible solution using the bioethical decision-making model. I would venture to say a single dentist has followed all three solutions (in the example above) at different points of her career.

Vague Answers

Is any solution more wrong than another? A solution would be obviously bad if it violated all the bioethical principles. This is a complex scenario with multiple solutions that violate a different number of principles while upholding others. If the situation was simple, the answer would be obvious. We need ethical reason when the situation is complex to answer, but the bioethical-decison making model does not always give objective answers.

Arbitrary Grounding

Each principle only acts as a suggestion for the doctor to consider. There is no reason these principles as vague as they are described obligate healthcare professionals in a moral sense. You will lose your license if you violate them. However, obligating someone through punishment signifies a rule is not moral in-itslef but rests on arbitrary consequences.

Objections: Case for Bioethical Principles

The flowing objections are taken from Raanan Gillon, professor of medical ethics at Imperial College London.

Objection #1 – The principles are prima facie.

What is prima facie common sensical and do not appear to have epistemic fault. It seems clear to anyone that one should be just, help other, do not do harm, take respect people’s choices. However, common sense does not make a moral theory true or valid.

This especially important when the conceptions of the bioethical principles are so vague they self-contradict. For example, justice can be expressed as both appeal to equality or fairness. Income redistribution promotes equality but not fairness. The principle of justice is so inclusive that it is self-refuting. It appeals to everyone because it expresses everyone’s contradictory intuitions.

Beneficence tells us to help but not clearly in what cases, maleficence tells us to reduce suffering but not to what extent, and autonomy tells us to respect things that are not worthy of respect. It is not adequate rational or moral justification for a moral theory just to be prima facie. It is not clear that the bioethical principles even are since they have so many philosophical objections.

Objection #2 – They are Designed for Healthcare Profesisonals

The four principles seem simple to use in fast-paced healthcare environments. However, the decision-making model doesn’t always give clear answers (example above). So, if multiple professionals are involved in a situation, they are still left in ethical conflict.

Bioethical principles supposedly avoid specific religious, political, or cultural standards, so doctors of all backgrounds can use them. We must remember, however, that the bioethical principles are a direct reaction to medical testing during the holocaust. So, they are inseparable from western religious, political, or cultural values historically.

It is claimed that health professionals still need simple principles even if they are general rules because they have so much to learn already. Without complex ethical education, health professionals are simply guessing at answers. We don’t hold doctors to easy guesswork when it comes to diagnosis or treatment. We should not hold them to casual moral reasoning when it comes to what is most important: doing the right thing.

Objection #3 – The Principles Avoid two Extremes: Moral Relativism and Moral Imperialism

Moral imperialism is the idea that there is only one way of doing ethics. Bioethical principles are flexible to allow for introjection of personal religious, political, and cultural values. Maybe there are multiple ways to do ethics validly and there is no one absolute method. However, to be one objective standard amongst many, you must still get consistent answers. People can correctly use the bioethical decision-making model and come to contradictory conclusions, each equally valid.

Moral relativism is the idea that any ethical opinion will do. Bioethics gives a standard for communication for healthcare professionals who have such different political, religious, and cultural backgrounds but are subject to a rational framework. The issue is that not everyone agrees on the principles themselves as they have no justifiable metaphysical grounding (i.e., establishment of truth or validity).

Reconciliation

Common sense is not what answers complex ethical questions. If its a complex or perplexing question, it doesn’t by definition have an obvious answer. Bioethical principles are simple but health professionals are smart and can handle rigorous ethical contemplation.

The principles as outlined are designed to be simple and open to interruption. What is seen as a valuable is actually a philosophical crutch. It is apparent that bioethical principles while avoiding absoluteness become vague and while proposing an objective standard fails to provide any objective justification.

The principles have to be clarified, not just new additions. The hope is a more rigorous model striving toward objectivity and rational grounding. Philosophy is a tool to search for objective truth in the face of skepticism. Ethics is a philosophical pursuit since ancient times and healthcare bioethics needs a philosophical re-awakening to be more functional and decisive.

Philosophical Exploration of Dentistry

Philosophy is the “love of wisdom” as coined by the mathematician Pythagoras. Wisdom is the propensity to come to correct conclusions to any specific problem using the correct principles, given theoretical or practical. Pythagoras observed that philosophers were those that seek truth to life’s most difficult questions. What is the right way to live, what is the human condition, etc. They would even take pleasure at mystery and seek knowledge for its own sake.

This may sound like a scientist to many. Science and what is now academic philosophy were both once the same endeavors. While science now studies the empirical world through the scientific method, philosophers study reality through the human construct using rational inquiry mainly. Philosophy is divided into three main areas (metaphysics, epistemology, and philosophy of language) and multiple subjects (esthetics, science, ethics, etc.). We do metaphysics to identify universal principles that give us answers to all particular conundrums. We do epistemology to evaluate the truth of those principles and how they were derived (human certainty). We express those principles in accordance to considerations in the philosophy of language.

Metaphysics

Many people think metaphysics is what is transcendental, what is “beyond the physical” or “outside spacetime.” Laypeople get this impression from pseudo-intellectual hippies. Academics get this impression from an etymological misunderstanding of “meta” and “physics.” Metaphysics, however, is the study of first principles: a set of propositions that explain the nature of reality as a whole.

The works of Aristotle have a big influence in western philosophy. His chapter on metaphysics directly follows his chapter on physics. Hence, the chapter on first principles was named because it literally is “beyond” or “after” the chapter on physics. Metaphysical discussions often involve discussion of non-physical or supernatural entities, but traditionally it has been the examination of the nature of reality.

Thales was the oldest recorded western metaphysician. Back then, philosophers were concerned with the scientific examination of the physical world. Living near the ocean, Thales observed empirically the importance of water in the ecosystem. Clouds (vapors) form rain (liquid) and seawater dries into salt (solid). He extrapolated that everything consists of water because everything relates to evaporation or condensation in some way. For Thales, the principle that governed reality was water.

Epistemology

How do we know if Thales was correct or incorrect? Questions that ask the certainty of a belief is in the realm of epistemology: the study of knowledge (episteme is greek for knowledge). Academic philosophy is mainly concerned with epistemology (e.g., how do we know we are not in the matrix) now-a-days. While thought experiments can be quite dry, we have to remember Socrates that used the dialectical method to examine his life and be a gadfly for the state

In epistemology, we are concerned with examining the viability of a method or gaining certainty. One of the most deeply root debates is between rationalism and empiricism. Roughly, rationalists (think of mathematicians) trusted pure reason to illuminate truth and considered the senses to be deceitful. Empiricists (think of observational scientists) tend to find meaning in only what can be seen, touched, etc. and find facts about the physical world to be inaccessible by reason alone. However, it is difficult to peg any philosopher solitary in one champ.

Rationalism and empiricism are perspectives that kind us to evaluate different modes of reasoning in different matters. We cannot be precise in our calculations if we measure the angles of a physical square object (but we know it to be 90 degrees by reason alone). It is also impossible to know the number of cusps of a first molar without every seeing one before in a human. Both the senses and reason seems to have difficultly in establishing knowledge (certainty).

Reason and Philosophy of Language

The last major division of philosophy is philosophy of language: how to express philosophical enlightenment. One greatest area of importance is logic symbolism. “n” stand for and and “u” for or are common examples of the development of logic. I will not give an in-depth course on first order formal logic but however I will focus on some logical principles and methods.

Modus ponens: If A->B, and A, then B

Modus tollens: If A->B, and not B, then not A

An argument is divided into premises and conclusions. The conclusions are derived from the premises through logical operations. For a deductive argument to be valid, the conclusion cannot be false if the premises are all true. If the conclusion could be false to any degree, the premise do not logically entail the conclusion. If an argument is valid and sound (i.e, the premises are all true), then the concussion must be true.

In speculative reasoning, we can be certain that a fact is true if the premises from which it is deductively derived are also true. The problem is to determine true premises also. Offering further axioms in proof of the original premises would entail further proof of those axioms. See the dilemma? Socrates used the dialectical method to somewhat help the situation. We first start with a common notion and attack it with counter arguments. If we end with a self-contradiction or it contradicts something known to be true then the first theory is rejected for a new reconciliation. Plato thought that the understanding from the rejections offered will develop a true idea (or at least a better one for reexamination).

Ethics

Aristotle – Virtue Ethics

Speculative Reason Vs Practical Reason

Aristotle makes the distinction between speculative reasoning and practical reason. As the name suggests, practical reasoning is not solely deliberation and knowledge but with maxims (a formulation of a goal and the means to achieve it) and action as end products of deliberation. In moral reasoning, we want to analyze deliberative processes that end in action since if a moral prescription were to be found true by speculative reason, there may not be any necessity for that action to be undertaken; in practical reason, the conclusion of deliberation cannot be conceived without action.

Speculative reason: All men are mortal (premise), Socrates is a man (premise), Socrates is mortal (conclusion)

Practical reason: All agents should tell the truth (moral principle), I am a moral agent (recognition of moral principle), tell the truth (action)

Aristotle is a well-developed proponent of Virtue ethics so it is important to considered his ideas. He taught important political elites at Plato’s Academy and then at his Lyceum, such as Alexander the Great. Virtue ethics deals with developing habits in people so they perform good actions in particular situations. There is an ancient idea that a good knife is one that is sharp (character trait) and so able to cut (perform its function well), so a good person is one with good character that so performs good actions. Aristotle claims that the good for a human being is found in the performance of a human function or activity well and since what is done well is in accordance with excellence (virtue), human good is performing human function with accordance with virtue.

The traditional set of four main virtues were wisdom, justice, temperance, courage from ancient Greece, though Aristotle (not greek) and many of the important Virtue ethicists have long lists of others. Habits are usually fixed reaching adulthood and only so much can be developed past out genetic propensities. It is easy to see that wisdom would be the most important virtue since the wisdom person would make the best decision but can perform the best action relative to her ability. Virtue (excellence) for Aristotle was a geometric between to excess. For example, in a situation that required courage, one should not be too cowardly not brash. Like a good archer one would determine the target the arrow, calculate the wind influencing the arrow and one’s one bias and then hit the target. Virtue ethics is very practical for individual people to run their lives and followers but is vague in answering ethical questions.

John Stuart Mill – Utilitarianism

John Stuart Mill might be the most influential ethical thinker to date. His consequentialist theory is the most applied in public health, businesses, and daily life. Consequentialists are only looking at the end results but they value different measures. Mill said happiness is the most final and sufficient end that justifies all our actions. If an action maximizes the amount of happiness that is the obvious one to take (the Utility principle). He urged readers to just look at Aristotle to gain clear understanding. Aristotle said that there was a final (the last thing referenced) and sufficient (provided value to) goal that all people aimed and that it was universal to all human beings. Take anything you do today and ask why what sake did you do it for? Let’s say you went to work for the sake of money. Money however is just paper and its value depends upon the things it can buy. Maybe you buy a car. Driving your car makes you feel joy. We can ask these questions of all human activity until we get to eudaimonia, happiness or well-being.

When pubic health officials do epidemiological studies, they define happiness in a metric like the number hospital visits due to tooth abscesses reduced by the introduction of fluoride in the water. They can determine what actions to take in a particular area. Using a utilitarian approach makes decision making much easier and easily adapted to empirical study and application.

Mill wanted people to think critically and understand that there one cannot seek anything of value just because it adds to your happiness; different things have different amounts and also qualities of value. One should rather study philosophy then binge on sugary cupcakes because cognitive activities are of high quality; Mill claims Hedonism is for swine. We are then able to derive certain principles from the main Utility principle. This is rule-based Utilitarianism instead of the simple act-based Utilitarianism where we are solely looking at the pure end results of a single action. While the thought that a principled ethic might be developed, if the actions determine the rule and if they vary by circumstance, then Utilitarianism is still only ruled by one principle, the Utility principle.

Immanuel Kant – Categorical Imperative

Kant is the most critical influencer of modern philosophy and ethics. Kantian ethics is a type of deontology, a duty based ethic. Kant claims that actions aren’t good by the expectations of their consequences but by following one’s duty. He analyzed our intuitions of duty and formulated the categorical imperative in four ways.

- The Formula of the Universal Law of Nature – Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law

- The Humanity Formula – Act in such a way that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of another, always at the same time as an end and never simply as a means

- The Autonomy Formula – The idea of the will of every rational being as a will that legislates universal law

- The Kingdom of Ends Formula – A systemic union of different rational beings through common laws

Kant proposed that nothing is unqualified except a good will. A good will is one that aligns itself with the concept of law as only true freedom is achieved through giving ones action the concept of law. Only rational beings can align their actions by concept of law and this is only though practical reason so thus the will is practical reason. I will go over the first two formulations as the third (governing one’s will by concept of law is to be autonomous) and the fourth is a summation of community of rational autonomous agents.

The first formulation of categorical imperative allows for two tests to determine duties. Practical reasoning relies on the consistency of will (disregarding agency as the source of moral claims) and consistency of practice or thought (scheme upon which the reality of the maxim is grounded) involved in the conception of the imperative. Take for example a person that wants to lie about a price because he wants to trick someone into paying more at his shop. This is a contradiction of will because the shop owner legislates that his will to have special access to truth while others not (his will is not in the conception of a universal law). This is also a contradiction of practice because a lie illegitimacies itself as the practice is willed universally (no one would believe a lie if it was legitimate to lie). A rational agent would act morally and not commit these contradictions of practical reason.

The second formulation tells us that people should be treated as ends, this means that people should be treated as agents that have legislative wills that can declare object moral laws. People should not be used, exploited, or objectified. The wills of all rational agents should be considered in decision making. Kantian ethics is an ethic of principles. Its difficultly is its utility in application but as one lives an examined life, one becomes more accustom to ethical deliberation and living an ethical life.