A Good Dentist

What makes a good dentist? The first thing that comes to mind is how skilled and smart the dentist is. However, a dentist may do very good crown preparations but may lie to patients for financial gain (skill vs virtue). The blog is not concerned about technical dentistry but ethical dentistry. Dentists seem to realize what the right thing to do most of the time, yet, choose differently. This is because they are merely told what to do and lack understanding of what makes something the right thing to do.

Ethics is the study of right and wrong but a more workable conception is the study of value theory. This article will discuss why morality is not merely an empty term but has underlying meaning as we give it. Dentists should learn not to be persuaded by embellished language but learn the underlying reasons why one ought to be good. While some philosophers appeal to ones own interest (what is valuable for the agent) to incentivize moral action, strict morality is based in obligatory worth (intrinsic value established through universal necessity). Proper understanding ensures moral behavior.

Dialectical Method

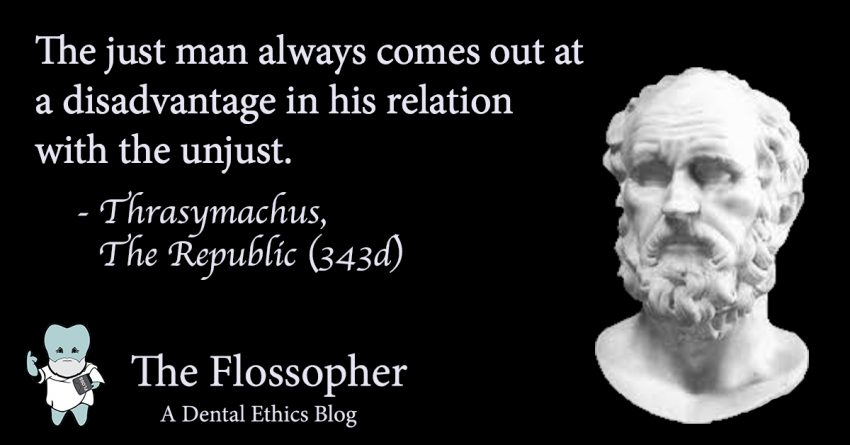

The Republic, by Plato, was historically the first full rational theory of ethical theory. The reason to be good is that it is by definition what one should do, and one should do what they should do. The question then becomes “what should one do?”. Socrates had a unique teleological argument. Improving the sharpness of a knife would make it more good because it is better able to fulfill its function. The right action for Socrates was to hone character traits (virtues) that improved an agent’s function. Being good was in one’s advantage since it made you better or best (improved well-being).

In the dialogue, Thrasymachus claimed that injustice was actually a virtue because just men took the high road so often they were taken advantage of. Many often judge moral actions to be below ones own interest. Socrates reminds us however that as injustice disrupts the unity in a group (e.g., one member cheats another) so for a person. An unjust man, falling into mental disruption, will ultimately make decisions counter to his own happiness. Personal justice for Plato was a regulation of the psyche to reach best action (well-being).

To ground altruism and general morality in personal interest makes for a viable theory to resolve conflicts. However, I must point out that like in an unjust society some are worsened for the sake of others, a just society that aims for the well-being of the whole will sometimes leave some members worser. Take for example, a just war (Plato claims for self-defense or growth one society can take the resources of another justly). The soldiers of this war may benefit the just society as a whole but would be worse and justice would not actually be in their personal interest to follow. We must find another reason why we should be moral.

Ought

Statements about the world (reality) can be either descriptive or prescriptive (sometimes both). Descriptive statements are concerned with what is the case (judgments of fact or truth) and prescriptive statements are what ought or should to be the case (judgments concerning better or worse).

It is what it is (a logical tautology) and can never be what it is not, so ethical theory cannot merely be descriptive if it is going to tell us what we should be doing. If I tell you that all dentists floss, it would be a naturalistic fallacy to claim that you should should floss (the disruptive statement contains no prescription). Moral statements must involve prescription if they are relevant to us at all.

I will point out that imperatives must be universal or general to agents in question for moral statements to be applicable otherwise other agents will not recognize the obligation (just because you should do something does not mean I am obligated to respect your action). I will also point out that if I tell you something should be the case, you do not know if I am prescribing what you may or could (possible and contingent) do or what you must (determinate and necessary) do. Strict moral statements are to be understood as the necessary oughts, since this means that the ought is obligatory (it must be followed) not merely suggestive.

Practical Reason

In ethics, we are not usually looking specially for truth statements. Obviously if a statement has a contradiction, it would tell us to do contradictory things (to follow it and not to follow it). We are looking for practical matters that affect us and help us to make decisions. What is “moral” or “good” tell us how to live life, a human life. Humans use practical reason (the will) to make deliberative decisions that result in action.

In the previous section, it was understood that strict moral statements have to be universal to be recognizable to other agents and necessary as to determine that action must be taken. “All agents A must do action X” would be a universal moral principle by which any particular agent (lets say Abe) would recognize the particular maxim “Abe must do action X” and conclude in action X. This is what is called a practical syllogism.

Morality is practical because it tells us what to do, that we need to do it, and others have to recognize this obligation. The meaning of morality is not an empty term but nominal for universal and necessary statements that tell humans how to live life.

Clarifications

One may object to such rigorous ethical analysis. Maybe we need practical reason for complex situations but most of the time people know what they want to do. I do teeth whitening because I find my teeth to be too yellow. We are motivated by our own emotional imperatives and they obviously apply to us. This view degrades when we think about harmful desires. I may want to eat a whole bag of jelly beans, but there is no obligation (no necessity) in that emotional appeal and the cavities certainly harm me. The other concern is that our desires are often products of external advertising. Emotional imperatives in-themselves are not obligatory (lack necessity) or even representative of our autonomous nature (lack universality).

All cultures, governments, religions, etc. claim, in some manner, to contain moral truths. Aren’t we safe to follow a moral theory already established? When we merely follow rules, we may think we are doing good but our actions are morally inert when we don’t have a morally legitimate intention directing our action (all physical actions are conditioned and not good-in-themselves absolutely). A religious or judicial law maybe morally correct in theory, but if I do not recognize its moral obligation (universality and necessity), then it is not I that is responsible for that action. Goodness can only be assigned to autonomous action while heteronomous action diverts responsibility to the originator. If an authority figure (dental associations or gods) commanded dentistry philanthropically and you provide free treatment without knowing rationally why, you would not thereby considered a good dentist (Euthyphro problem).

One may then ask how we analyze if a statement is universal and necessary. Merely claiming any action in an “all” and a “must” form does not make a universal and necessary statement under practical reason. Claiming “all agents must murder” does not actually make it so because it commits practical contradictions. Kant outlines two contractions, one of will and one of thought. Willing that the murder lives while the victim dies uploads different rights to different agents, so this maxim cannot be universal. Murder, by its nature, is a negation of a will itself (you can’t will if your dead) so violates the grounds by which the maxim is made legitimate, so the maxim cannot be what an agent necessarily ought to do ever.

Autonomy

At the start, I presented the classic distinction between skill (a technical good) and virtue (moral good). We can better understand morality by introducing the distinction between moral good and praise. When someone accidentally does good, we do not consider them to be moral but we can praise them. The same is true when someone commits an accident; they are not evil creatures because they didn’t intentional do wrong but they are still blameworthy. A good dentist is one that intentionally does good.

Kant explains that one does a moral action not because one merely wants to but one recognizes it as a duty (unqualified or unconditioned maxim). One formulates her will in the form of the the moral law (i.e., universalize your maxim as a universal moral law of nature) and so acts autonomously since her will is in the form of law (autonomy means “self” “law”). Noting qualifies (is worth greater than) a categorical imperative, so an autonomous will always does best.

A law, for Kant, is a necessary rule (not some possible way a thing works, but a way it must work). A rational will is how humans direct action autonomously when an action is universalized in the form of a moral law. Since it is universal, it is certainly applicable to all human wills and recognizable by all rational agents. Since it is necessary (being in the from of law), we are all obligated by it and all rational agents must respect it.

Conclusion

You may feel like something is moral and other people may agree with you. However, if you merely do the action because you are told to do so or emotionally motivated and do not recognize a rule’s universality or necessity, you are not deserving of moral responsibility or praise. Only acting autonomously (a rational will that recognizes a command as a universal moral law – necessary rule) can you be regarded as a good person absolutely and your actions correspondingly.

One must be moral because it is obligatory (it applies to everyone and it must be followed since it contains universality and necessity – conception of law). Kant illustrates how using the categorical imperative results in moral truths. Categorical imperatives have intrinsic, unqualified/unconditioned (infinite) value, so is the best thing to do for rational agents and must be respected by all rational agents. Being moral is always best and always in your best interest.

For any action to be worth taken, one must act from a conception of the moral law under the will. For one’s will to be respected, the will of others must be respected universally and a will that universally respects must itself be respected. This reciprocative and regulative principle of the psyche might be an enlightening advancement in Plato’s eternal search for the form of justice. For dentistry, the foundation of a patient-doctor relationship is respect, not for just anything, but for a rational decisional making process.

Author

Dr. Vishnu Burla, DDS, BA Philosophy

Further Reading

Intro to Dental Ethics. Aristotle and Mill presents happiness as the purpose of human life. Kant does not disagree but adds to this ethical concept with the categorical imperative.

Grounding of the Metaphysics of Morals by Immanuel Kant

The Highest Good: Respect for Humanity. Read why respect for humanity is the most valuable thing in the world.

Facebook Comments